THE STAGE 32 LOGLINES

Post your loglines. Get and give feedback.

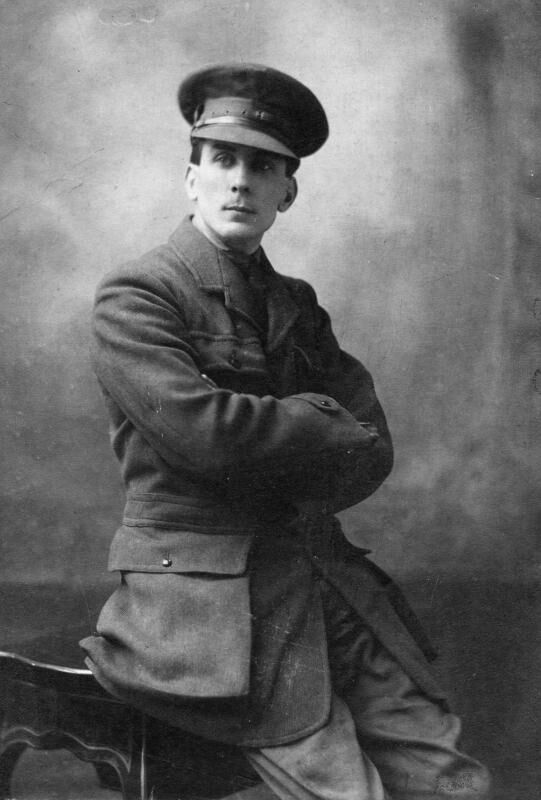

HOW I FILMED THE WAR

By Alex Gwyther

When filmmaker Geoffrey Malins is sent to the Front Line armed only with a camera strapped to his back, he must help Britain win the war by filming one of the bloodiest battles in British history, and returns with the first blockbuster in British cinema.

SYNOPSIS:

Based on his memoirs, HOW I FILMED THE WAR is a biopic feature of how Geoffrey Malins risked his life to film The Battle of the Somme - the first Blockbuster in British cinema, and how he is responsible for the lasting footage of the First World War today. It is a salute to the birth of documentary filmmaking, an insight into early war correspondence and captures Malins’ sacrifice and impassioned endeavour to use cinematography to document the war.

Geoffrey Malins starts as a talented but frustrated cameraman stuck shooting topical newsreels. He yearns to be acknowledged as a revered and celebrated filmmaker, believing his films could change the world, but blames the War for why he isn’t getting the recognition he deserves. At home, Malins sits in silence with his wife, Caroline, at dinner; he tucks his children into bed and reads them stories, but his mind is always occupied on his cameras, his films, his passion.

When Malins is summoned by the War Office, his experience filming the Belgium Army and his blazing obsession with cinematography make him the perfect candidate to be the nation’s Official War Cinematographer. His mission: to go over to France and film actual footage of the conflict to win the propaganda war and recruit more soldiers. Malins refuses, believing it will further exacerbate his ambition to create his own films, but is forced to accept when he is given two choices - join as a cameraman or as a soldier.

Upon arriving in France, Malins is met with stern scepticism from Officers who don’t understand the need for a camera in the trenches. Malins is given a young assistant, Berry, whose job is to escort Malins across the Front and keep an eye on him. Sharing a mutual love of film, they strike up a friendship and Berry becomes Malins’ mentor, teaching him new skills to help him survive on the Front. Malins experiences bombardment for the first time and witnesses the horror of Front Line warfare. However, when Malins risks his life by carelessly putting his head over the parapet to film a scene, Berry is shot through the head as he tries to stop Malins from exposing himself. Malins’ ego-led grand ambitions of fame are quickly obliterated as he blames himself for Berry’s death, understands the futility of the conflict and the huge unnecessary loss of life.

Malins returns home with the footage he’s captured and returns back to work; his fingertips shaking as he edits newsreels of men smiling in training camps which don’t depict the first hand horrors he witnessed. He isolates himself from Caroline and the children, while his dreams of becoming a revered filmmaker quickly dissipate. He throws away his scripts and attempts to sign up for the army, but loses his nerve and flees the queue, knowing what lies waiting for him in France. He is not built to fight. He is built to film.

But, what Malins fails to recognise is the positive reaction to his work - praise from politicians, an increase in new recruits and the morale of the nation brightening. The War Office approach Malins to send him back to the Front Line. This time, he is to create a propaganda film on an upcoming offensive which will change the face of the war - the Battle of the Somme. Malins returns to the Front Line with renewed vigour and inspiration as he understands that his purpose as a filmmaker isn’t to serve himself, but is subsumed to serve a greater more tangible truth of human sacrifice. Now, he is more experienced of the horrors of the Front and resolute to capture the heroism of the men for the British public. Malins films for three days without rest. He is targeted by German snipers, shot through the hat, deafened, gassed and unnerved by bombardment, but returns with over 8,000 ft of footage strapped to his body.

With a deadline issued to deliver this vital piece of propaganda before the war is lost, Malins tirelessly revisits and edits the traumatic scenes of men dying and going over the top. In the process, his relationship with Caroline and his children completely breaks down as he becomes obsessed with finishing the film, spending days away from home and only occasionally returning to wash and change his clothes. All the while, Malins feels like a fraud - he is not a soldier, he is a civilian who has briefly experienced a soldier’s hell. Things are made worse when part of the film is unusable due to limitations in the cinematic technology, and the War Office orders the scenes to be “faked” with soldiers in a training camp - a stern reminder to Malins that he is making a propaganda film, further conflicting with his artistic endeavour to capture the truth. On the film set, Malins, as the director, screams at the actors, pushing them to their limits to mimic the ferocious landscape of battle.

On 10th August 1916, The Battle of the Somme premiers in London to a spectacular reception. In the coming weeks, 20 million people (half the population) queue outside cinemas across the country, making it one of the most successful films ever released in British cinema, blazes an obsession for fictional war dramas and ignited the British cinema industry. It gives birth to the term “documentary filmmaking” and sets a national standard of war correspondence. After the war, Malins is awarded an OBE for undertaking his work “in circumstances of great difficulty”. His dream comes true; he is finally recognised as a respected filmmaker, but at the cost of his family and his health.

Rated this logline

Rated this logline