THE STAGE 32 LOGLINES

Post your loglines. Get and give feedback.

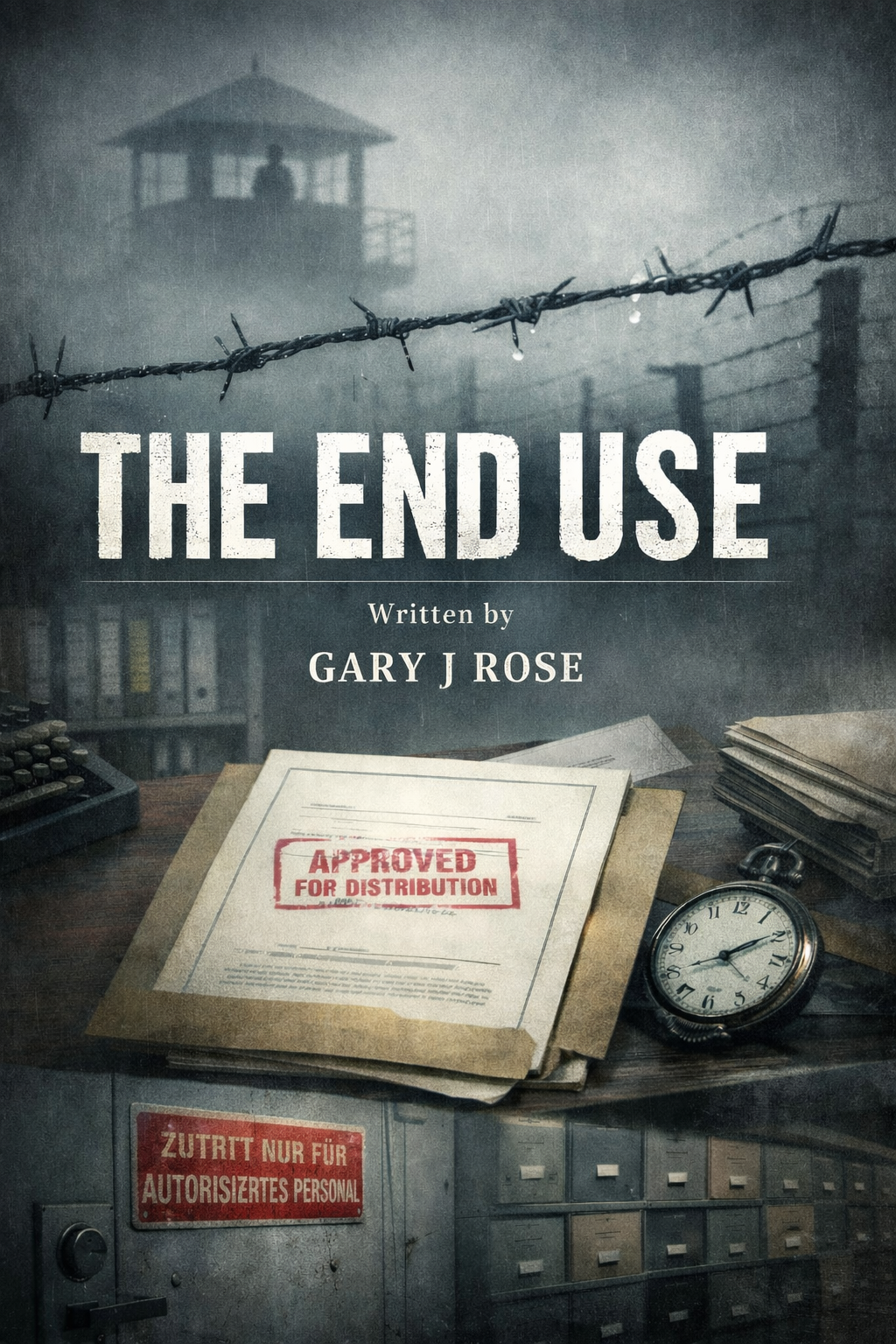

THE END USE

By Gary Rose

When a German industrial chemist discovers his product is being quietly repurposed for mass murder, his greatest defense is not denial — but the language of compliance that allows the system to function without conscience.

SYNOPSIS:

The End Use is a restrained historical drama examining how genocide was enabled not only by ideology, but by language, distance, and procedure.

The film opens not with victims, but with process: rain falling on barbed wire, a watchtower emerging from fog, machinery humming beneath an industrial roof. An unseen act occurs — implied, never shown. The horror is present only through its mechanics.

We then meet Hans Keller, a German industrial chemist and senior corporate functionary. He is meticulous, calm, and unremarkable — a man whose life is defined by documentation, approvals, and compliance. Keller does not design weapons, issue orders, or visit camps. His responsibility lies in ensuring that a chemical product moves smoothly through a lawful supply chain.

The chemical is Zyklon B.

As Germany collapses and the war ends, Keller continues to operate within the same professional logic that has governed his career: responsibility is limited by jurisdiction, legality defines obligation, and intent is irrelevant once a product leaves his control. At home, his wife Ellen senses the growing moral void behind his precision. When she asks whether the recipients of the chemical understand its purpose, Keller responds with the language of insulation: determinations are not his to make. Someone always decides. The conversation ends not in argument, but in silence — the first sign that Keller’s language fails outside institutional walls.

Following the war, Keller is arrested and brought before a tribunal investigating the industrial mechanisms that enabled mass murder. The prosecution does not accuse him of hatred or violence. Instead, they dismantle the bureaucratic framework that allowed men like Keller to remain untouched while millions were killed.

Through testimony from logistics officers, administrators, and corporate executives, the court exposes a system built to fragment responsibility until it disappears. Each participant followed rules. Each step was approved. Each decision was legal.

Keller prepares to testify as he always has — carefully, precisely, with language designed to deflect inference. But before he takes the stand, the prosecution anticipates his defense, reframing compliance itself as an instrument of concealment. For the first time, Keller realizes that the very logic he authored is now being used against him. His language no longer belongs to him.

On the stand, Keller does not confess. He does not deny. He explains. He insists that regulation exists to prevent chaos, not assign guilt. That responsibility diminishes with distance. That morality is not a regulatory category. His testimony is chilling precisely because it is coherent.

The tribunal’s judgment is mixed. Some individuals are convicted. Others receive reduced sentences. Many return quietly to private life. The system that enabled the crime survives intact.

The film ends not with catharsis, but with acknowledgment. Title cards reveal the scale of the atrocity, the lawful channels through which it was executed, and the uneven consequences faced by those involved. The final statement is simple and irrevocable:

The end use was known.

The End Use is not a film about monsters. It is a film about systems that work perfectly — and the people who hide inside them.

Great opening clause sentence that caught my interest, however after that first comma it loses me. It falls into the obscure and hard to comprehend. You don't want to be too obscure; give us more about the conflict to his want, reveal more of the specific journey rather than vague terms like "language of compliance" and "function without conscience" which are difficult to ascertain or apply to your story. Hope this helps. By all means PM me if you'd like to talk further.

Rated this logline